Measuring ROI in a law firm - even if it's possible, does anyone care?

/Many organizations do a poor job of measuring the return generated by their various investments. As a result, many initiatives fail to deliver impressive results even while the organizations as a whole are performing well. Imagine a professional sports team that measures only wins and losses and ignores individual statistics such as points scored, penalties assessed or defensive lapses. How do the coaches know who needs help? How does the general manager know who to reward handsomely with a new contract? How do the players know what skills to hone in the off-season? Obviously a quality sports team will focus on a myriad of individual elements that, combined correctly, produce wins, and, combined poorly, tend to produce losses. Measuring the return on investment (ROI) of our various expenditures should be viewed in the same light. After all, if we don't measure how well or how poorly our many initiatives are doing, how can we improve our performance? As the late legendary Coach John Wooden used to say, "Failure is not fatal, but failure to change may be." I conduct workshops on this topic regularly to different audiences, including law firm technologists, marketers, directors of finance, partners and in-house counsel. While the ROI discussion may vary depending on the stakeholder, there are a few common themes.

Measuring ROI may not require heavy math, but it very likely involves stepping out of your comfort zone. The classic example comes from the advertising world where the creative types at agencies devise compelling advertising that catches the eye but may not provoke buying behavior. As one CEO scoffed when presented with a visually rich and quite expensive campaign idea, "I don't care about creating art, I care about moving units." In a law firm, a technologist may feel upgrading to the latest voice-over-IP phone system is long overdue, but given the considerable expense and time needed for a firm-wide upgrade, it may require a financial analysis plotting the cost of maintaining an older phone system against the cost and benefits of the upgrade. A law firm marketer asked to produce a client alert for a news item that every competitor discussed weeks ago may have to (gently!) push back by demonstrating that the optimal window to maximize "click though rates" has long since passed. ROI discussions often involve the mastery of different dialects to make the case to others.

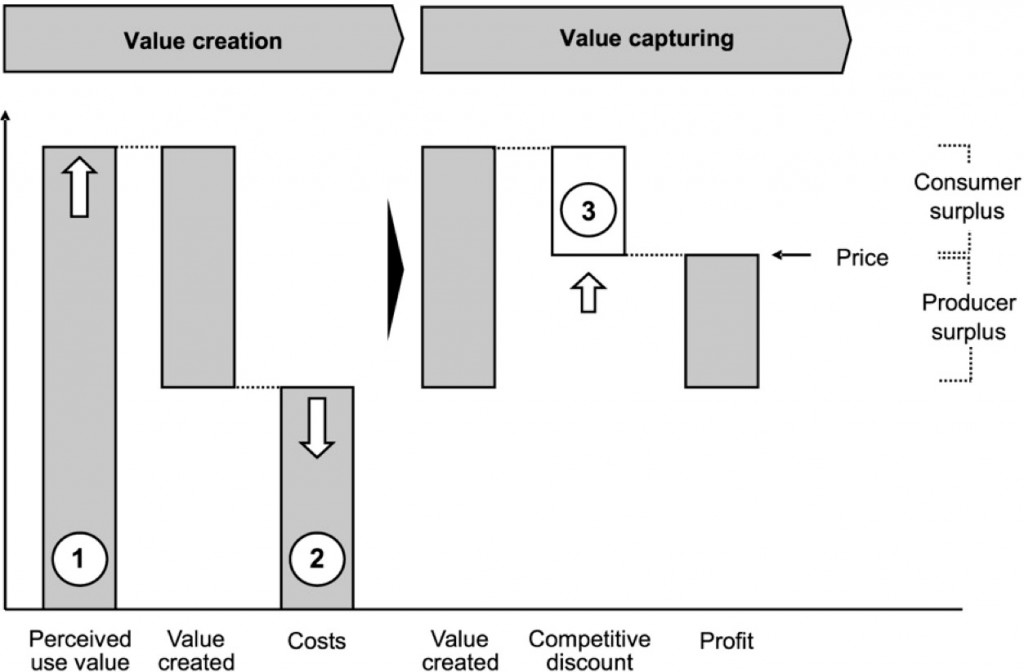

ROI is a relative measure, not an absolute measure. In a basketball game if Joe pulls down 5 rebounds per game and Andre pulls down 6, who gets the coach's praise? What if we learn that Joe is 6 feet tall and Andre is 7 feet tall? If all other factors are neutral, we should expect Andre to significantly out-rebound his shorter peers. In this light his performance is not very impressive. If a law firm hosts a seminar that draws 15 people, is that good? If we invest $2 million in three lateral partners and they deliver $2.5 million in new billings in year one, is that acceptable? There is often not a specific hurdle past which everyone can objectively state that "We achieved a successful ROI." It's only by comparing the ROI of an initiative to alternatives that we can ascertain whether the ROI is acceptable or not. If the 15 attendees of our seminar represent top-level decision makers at target prospects, this might be a much better investment than a larger event with 90 client attendees representing staff lawyers with no input on outside counsel selection. What if we delayed implementation of a key client program by two years in order to invest in our lateral recruitment, but even a conservative estimate of our cross-selling forecast suggests that we could have generated $5 million in new billings from existing clients? Were the lateral recruits such a good investment after all? Good organizations compare the relative ROI of various initiatives and the best ideas must earn the capital investment.

ROI can only be measured over time. Law firms generally operate on a cash accounting basis, which involves counting revenues and expenses one year at a time and distributing excess (a.k.a. profits) to partners annually. This forces a one-year-at-a-time mindset, whereas most businesses operate on an accrual basis, which makes it much easier to consider investments over a longer period. Imagine the junior partner, looking to improve his networking at the country club, who takes a golf lesson. At the end of the lesson if he hasn't dropped his handicap from 30 to 5, he typically doesn't quit in disgust because he recognizes that improvement takes time. Yet this same partner may sit on a cost-cutting committee that votes to "eliminate the trust & estates practice group because last year it wasn't as profitable as other practices." But simple analysis may indicate that 35% of our highest-revenue litigation cases come from companies whose CEOs are T&E clients. And of these CEOs, 60% were T&E clients first, indicating that the T&E practice is an effective feeder for the litigation group. Removing this feeder skyrockets the "cost of sales" for the litigation group, instantly eliminating any savings from disbanding the T&E group. Your mileage may vary, of course, but only by studying trends over time can we make these connections. By viewing ROI as a snapshot in time, we tend to make flawed decisions.

There's so much more to say on this topic and it's particularly needed now, as law firm leaders are scrutinizing expenses across the board and struggling to find the right formula to generate profits. One universal challenge is that measuring ROI forces us to address sacred cows, those pet expenditures that we just know are good ideas but that no one can prove. Telling a partner that he cannot continue to invest in a luxury sports box is a lot more challenging for the executive committee than laying off secretaries, after all. But the bottom line is that measuring ROI allows us to make informed choices about where and how to spend the firm's capital... even if some of the final decisions are dumb ones.

For legal technology readers, feel free to join me as I conduct a webinar with ILTA on August 7, 2013 at 12 PM ET on this topic. For more information and to register, click here. Others can click here to read a recap of a recent presentation I delivered to legal marketers in Chicago, thanks to Sania Merchant and the National Law Review.

Timothy B. Corcoran delivers keynote presentations and conducts workshops to help lawyers, in-house counsel and legal service providers profit in a time of great change. To inquire about his services, click here or contact him at +1.609.557.7311 or at tim@corcoranconsultinggroup.com.