The Fallacy of Merger Math

/In recent months, trade publications have been filled with breathless accounts of the exciting and unprecedented number and nature of law firm mergers, each of which creates a distinct advantage over moribund competitors and, naturally, the financial outlook of each merger is rosy. Two firms with overlapping global footprints have joined forces to take advantage of the obvious synergies; two firms with not a thing in common have joined forces to exploit the obvious opportunities; two firms with fundamentally different compensation systems have joined forces without conflict by embracing a novel corporate form that eliminates the mingling of profits; two firms whose respective client bases are perennial adversaries have joined forces because the combined industry expertise of the merged firm’s lawyers will outweigh any potential client conflicts; and so on.

There is always optimism at the inception of a law firm combination, since few partners or clients would embrace a combination positioned as "a last-ditch effort to improve partner compensation when all else has failed."

If we were to analyze law firm mergers by plotting client satisfaction on one axis and partner satisfaction on the other, the resulting scatter diagram would reflect a surprising few combinations that were deemed satisfactory after the fact to all parties. This isn’t limited to law firm combinations; indeed, many corporate mergers go awry for similar reasons including poor execution, loss of key talent, loss of key clients, boardroom battles, mismatched cultures and failure to achieve financial targets. So why do law firm leaders continue to pursue mergers at such a furious pace? It’s a basic law of finance — when you have eliminated all other drivers to achieve growth but one, leaders will pursue the remaining driver with vigor, and call it a strategy. Let’s break this down a little further.

Fundamentals of Law Firm Finance

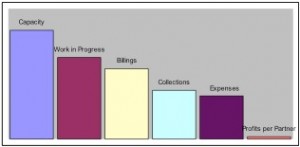

The basic drivers of traditional law firm finance are captured in the acronym R.U.L.E.S., which stands for Realization, Utilization, Leverage, Expenses and Speed (of collections). Each plays an important role in transforming the raw material of lawyer capacity (time) into profits per partner.

Realization

can refer to the relationship between hours worked and hours billed, or between hours billed and hours paid. In both cases, there is a fall-off. Not all hours utilized can be billed, and as clients have made abundantly clear in recent years, not all hours billed will be paid in full.

Utilization

describes the relationship between available hours and hours worked. A high utilization rate means that few timekeepers are idle, hopefully occupied with billable activities.

Leverage

is the ratio between partners and associates or other timekeepers. With high leverage, more work can be pushed down to lower-cost timekeepers. With low leverage, partners tend to retain and bill more work, even work that might not otherwise justify partner rates.

Expenses

are a huge factor in any law firm, and the largest category by far is personnel, notably lawyer and staff compensation. But real estate, equipment, supplies, artwork, coffee, a subsidized cafeteria and any other non-reimbursable expenses are accounted for here. This category tends to receive the most scrutiny during a downturn, although poor utilization and realization further upstream generally have a far greater impact on profits.

Speed

of collections refers to the process of billing and collecting receivables from clients, a process in which lawyers as a profession are notoriously lax. There is lag between doing work and capturing time entries; lag between capturing time and preparing pre-bills for partner review; lag between pre-bill review and customer invoicing; and lag between invoicing and receiving payment. The combined effect on law firm profitability can be enormous, albeit hidden to most.

The ‘Waterfall Effect’

These five factors inter-operate in a  sort of "waterfall effect," starting with the self-imposed revenue cap that law firms choose and, as each factor is deducted from this maximum starting point, ending with profits per partner, a simple calculation derived from dividing remaining profits by the number of partners. What’s that, you say? A self-imposed revenue cap? Few partners, even those tasked with managing their enterprises, seem to understand the nuances and limitations of the hourly billing-based financial structure. And this gap in knowledge has led to an increase in merger-as-strategy at the same time it has limited the growth of alternative fee arrangements, in the misguided impression that any such non-hourly structures are by nature dilutive to earnings.

sort of "waterfall effect," starting with the self-imposed revenue cap that law firms choose and, as each factor is deducted from this maximum starting point, ending with profits per partner, a simple calculation derived from dividing remaining profits by the number of partners. What’s that, you say? A self-imposed revenue cap? Few partners, even those tasked with managing their enterprises, seem to understand the nuances and limitations of the hourly billing-based financial structure. And this gap in knowledge has led to an increase in merger-as-strategy at the same time it has limited the growth of alternative fee arrangements, in the misguided impression that any such non-hourly structures are by nature dilutive to earnings.

Maximum Revenue

Law firm leaders can calculate the maximum revenue at any time by multiplying the number of timekeepers by their individual hourly rates and the number of available hours. Period. Clients tend to question invoices reflecting lawyers billing more than 16 hours in a day, let alone 24 hours in one day. Clients have for several years now pushed back strenuously on increases in billable hour rates. So what’s left to increase revenue? Increase the number of available hours to bill, which, said another way, is add more timekeepers. In past years when demand was high, adding another timekeeper was synonymous with adding 2,000 (or more!) billable hours. Now the emphasis is on laterals with portable books of business. In other words, adding potential billable hours isn’t enough, we need to add actual revenue-producing hours, and the easiest path to doing so is not to induce clients to hire us more frequently, but to transfer existing billable hours from another firm to our own.

A key challenge with this approach is that mergers tend to be a revenue solution to a problem that most law firm leaders, and partners, would characterize as an issue of declining profits. Imagine Firm A, which is loathe to merge and grow outside its comfort zone. Instead, it focuses on the other financial drivers in order to boost profits. Contrast this with Firm B, which combines a large-scale cross-border merger with numerous fill-in lateral acquisitions that increase headcount and revenue.

Firm A improves its profits per partner by 12% while maintaining the same practice and geographical footprint, culture and values. Firm B doubles in size, creating a cacophony of competing cultures, practices, tools, philosophies and, its leaders realize too late, almost no economies of scale beyond a few redundant staff roles. After all, each timekeeper and staff person requires compensation, a desk, a computer, coffee, et al. Indeed, all the combination has done is increase the size of both the numerator and denominator in the profits-per-partner calculation. What remains are similar, perhaps even lower, profits per partner despite the larger revenue streams because of the larger expenses and higher number of partners sharing in the proceeds.

Improving profits without resorting to the faux ami of a merger can be accomplished by tackling each of the financial drivers. Here are three tried and true techniques that disciplined law firms employ:

1. Identify and isolate sources of realization "leakage."

Most firms allow partners to write down invoices before sending to clients, often because a matter "feels" overbilled. Firms employing legal project management have a clearer understanding of the value of certain tasks and prohibit write-downs when tasks fall within budget guidelines. Similarly, many lawyers fail to capture all hours worked, under the notion of protecting clients from inefficiency, and so the hours captured and eventually billed don’t reflect the actual time spent. However, it’s important to capture all hours and then apply a disciplined review process to eliminate inefficiencies. If an associate spent 10 hours on a task budgeted for 5 hours, it’s as important to capture the 10 hours as it is to avoid overbilling the client. Through proper accounting, the firm can better identify training needs and tweak inaccurate budget assumptions.

2. Link collections to lawyer compensation.

Many firms apply severe punishments to associates who fail to promptly capture time entries, but far fewer have programs in place to police partners’ collection efforts, though they are really two sides of the same coin. Corporations short on cash sell their accounts receivables at a discount to "factoring" companies that then aggressively pursue collections. What makes this practice profitable is the immutable law that with the passage of time the expected percentage of receivables collected declines steeply, so factoring companies that pursue speedy collections can be hugely successful. By contrast, law firms that wait until the end of a quarter or end of a fiscal year to collect outstanding invoices write down a substantial portion of fees in order to accelerate payment.

Clients (or their AP departments) know this and will happily sit on an invoice until it "earns" a 25% or even higher discount. In some firms, the dilutive impact of delayed collections is substantially higher than the higher-profile expenses that cost-reduction committees tend to target, such as staff ratios, travel expenses, etc. Some firms won’t allow draws for partners with receivables over a certain age. Others limit partner discretion in negotiating discounts, or factor steeper discounts into compensation formulas.

3. Monitor leverage for hoarding.

This is sensitive, if only because "hoarding" hours is as much a question of judgment as of analysis. But there are certain tasks that are undoubtedly not economic to be conducted by partners, when a lower-cost associate is available to do so, and vice versa. The lower realization on these tasks is a clear signal that the clients have corrected, after the fact, a misplaced assignment. Again, the firms employing legal project management have a more refined sense of the market value of specific tasks and can more closely monitor assignments. Low leverage tends to lead to higher profits in the short run, because clients are ostensibly paying higher rates. However, analysis tends to reflect the longer-term dilutive impact from price-sensitive clients who fail to return, a result that increases the cost of sales for the next engagement.

The rush to law firm mergers strikes many lawyers and journalists as a tactic that needs explaining in strategic terms, but, in fact, in most cases it’s simply the most expedient way to boost top line revenues, which law firm leaders hope will translate to increased profits. But law firm leaders relying on insightful analysis of their own microeconomics will better understand that magnifying inefficiencies and lack of fiscal discipline won’t boost profits as quickly and effectively as instituting more rigor in the law firm’s business practices.

Partners aren’t typically trained in finance, yet we expect them to make battlefield decisions every day that impact profits. A little guidance and a few carrots and sticks applied in the appropriate areas can deliver both profits and peace of mind to lawyers who prefer to avoid growth for the sake of growth.

A version of this article was originally published in my Leadership in the Law column for Marketing the Law Firm, an ALM publication.

Timothy B. Corcoran delivers keynote presentations and conducts workshops to help lawyers, in-house counsel and legal service providers profit in a time of great change. To inquire about his services, click here or contact him at +1.609.557.7311 or at tim@corcoranconsultinggroup.com.