One of the trending phrases in the legal marketplace is "big data," which refers loosely to the synthesis of massive amounts of data, often from disparate data sets, to provide leaders with predictive analytics and better decision support. While this has been the norm in business and industry for decades, only recently has there been a compelling need for law department and law firm leaders to embrace advanced business practices. The opportunities for a "big data" approach to provide a competitive edge are many, in large part because so few do it well.

What is Big Data?

The definition of "big data" varies depending on the audience. In a sophisticated corporate environment, big data might refer to analyzing and cross-referencing customer purchase trends to predict that a buyer of product A will likely be interested in product B. We see this all the time with Amazon.com's personalized recommendations based on a customer's past purchases or even browsing history: if you purchase a book of baby names, you are likely to see recommendations for books, clothing and sundries related to the care of newborns. This approach can be startling effective.  In a law department or law firm environment the analysis might be more rudimentary, but can still provide excellent guidance. For example, many law departments now employ dashboards to identify the average length and cost of similar legal matters, and this influences how much they budget, and what outside counsel fees they're willing to pay for representation on a matter. As Jobst Elster asks in his "Big Data: Hype, Reality, Myth or Legend" article, "Can businesses -- including law firms -- even compete, let alone exist, without a big data strategy?"

In a law department or law firm environment the analysis might be more rudimentary, but can still provide excellent guidance. For example, many law departments now employ dashboards to identify the average length and cost of similar legal matters, and this influences how much they budget, and what outside counsel fees they're willing to pay for representation on a matter. As Jobst Elster asks in his "Big Data: Hype, Reality, Myth or Legend" article, "Can businesses -- including law firms -- even compete, let alone exist, without a big data strategy?"

Big Data for Law Departments

Most law practices are by nature reactive. The in-house counsel don't know in advance what products liability suits will be filed or what transactions management will pursue, so the lawyers stand ready to tackle whatever might come their way. But some in-house counsel are looking into the business itself for leading indicators. One in-house lawyer I recently interviewed reviews production quality control data with manufacturing line managers in order to better understand the nature and frequency of product defects that are likely to have shipped. She combines this with customer service call histories, which are coded by product lines and model numbers, to chart the emergence of these potential defective products. This insight allows her team to develop proactive strategies, from product recall to settlement analysis to hiring defense counsel in advance of the first suit. Another General Counsel sits periodically with his colleague, the VP of strategy, to review the list of potential acquisitions, and then his team compiles a very brief dossier on each target indicating the relative legal complexities of the transactions. Not exactly deep analysis, but a step in the right direction.

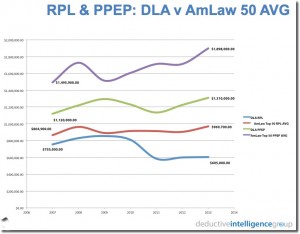

More advanced legal departments seek to identify patterns related to positive legal dispositions, and then redirect outside counsel in related matters to apply the techniques that have worked elsewhere. Others employ predictive analytics to more quickly identify when a case should be settled rather than litigated, and employ other predictive analytics to accelerate the settlement negotiation process. Craig Raeburn of TyMetrix, which provides data and analysis to law departments and law firms, confirms that "using benchmark analytics to improve performance and transparency and create competitive intelligence is the next great frontier in the legal industry."

Big Data for Managing the Law Firm Business

One of the more ridiculous tenets of law firm business generation is that "all revenue is good revenue." In a disciplined corporate environment, many top law firm rainmakers might be perceived as marginal contributors because the deals they bring in, while numerous, may incur high costs to service and therefore the contribution margin of the work is dilutive. But law firms typically reward origination, not profitability, so a partner generating $5 million in new fees with a profit contribution of $0.5 million often will be rewarded far more handsomely than a partner delivering $1 million in profits on a $2.5 million book of business. By adding the cost of delivery and the cost of pursuit (what it takes to win the work) to a matter's hard costs and allocations, and then comparing this against the top line revenue, law firm leaders are better able to identify the matters, and the lawyers, who contribute the most to the bottom line.

Law firms have also begun to employ a big data approach to identifying the "ideal" client. While this definition varies from firm to firm, it generally encompasses clients generating profits from multiple matters over time rather than from one matter, and clients with legal needs spanning multiple practices and requiring numerous partner relationships rather than those with one key rainmaker tied to one key decision maker. A firm that can be more precise with its client and prospect targeting can improve profitability merely by walking away from dilutive work, and avoid raising rates. The analytical rainmaker will identify the characteristics of the ideal client, then identify prospects matching this profile, and then work with the marketing team on successful tactics to pursue these prospects. Contrast this with the "traditional" approach to rainmaking where we talk about our capabilities to anyone we can, with the knowledge that sooner or later we will find a prospect in need of these capabilities, and you can see how an informed approach can easily surpass the results of a "shotgun" approach to rainmaking.

When it comes to business development tactics, partners tend to hold the marketing team more accountable than they hold themselves for achieving some elusive return on investment, or ROI. However, a big data approach to measuring ROI can level the playing field. One firm deduced that prospects or past clients who subscribe to 2 or more practice newsletters and attend 3 or more events are 75% more likely to retain the firm than an average prospect. So when the marketing team identifies a prospect with the "right" newsletter subscriptions but who hasn't attended the "right" number of events, the prospect is flagged and a partner will personally call to recruit the prospect to an upcoming event. With such an approach, the firm has significantly improved its financial performance. Alina Gorokhovsky, who advises government departments and agencies on the use of data analytics to transform government and who previously served as a law firm Chief Strategy Officer, is a strong believer in data-driven decisions: "No law firm should operate in a fragmented fashion, with every practice group and office pursuing any client for any matter simply to grow revenue. A more rigorous approach based on analyzing internal and external data will reveal clear benefits in pursuing the right clients, with the right tactics, for the right matters."

In case it's not self evident, many law firms struggle with adoption of alternative fee arrangements, believing many to be dilutive to a profit stream that has long prized hourly billing. Kris Satkunas in a recent Inside Counsel article offers some excellent insights into the benefit of big data to inform alternative fee analysis. Chris Emerson of Bryan Cave offers additional insights into big data and law firm profitability in this Information Week article. At the recent P3 conference hosted by the Legal Marketing Association, numerous experts offered commentary on the natural connection between analytics and profitable decisions. And the list goes on.

Big Data for Managing Talent

Many law firms employ a growth strategy best described as "recruit lateral partners with portable books of business." With such an indiscriminate mindset, it's no wonder that many law firms recruit laterals who don't fit the firm's culture or don't actually bring in as much business as promised. And they often find that those who do deliver a robust book of business require a high cost to service, which is dilutive to profits, or whose new clients create conflicts with existing clients, so the net positive financial impact is minimal. It may seem unrelated, but recruiting associates often follows a similar pattern: recruit top students from top schools, often without regard to practice interest or personality, and rotate them through various departments until they find a home where they can toil away until making partner... although an overwhelming number depart long before making partner. This approach isn't unique to law firms, as law departments often hire skilled technicians in certain areas of law under the assumption that, say, if we're an investment bank then an in-house lawyer well-versed in securities law is a good fit.

The reality is that law firms and law departments, like any other organization, have a certain personality, and succeeding in any environment has as much -- if not more -- to do with matching behavioral characteristics than with technical considerations. Savvy law firm leaders are increasing the importance of cultural fit when recruiting laterals -- after all, if the ideal client is one with matters spanning multiple practices, then a lateral with a $5 million book of business who refuses to collaborate or provide access to her client is not as good a fit as one with a $1 million book of business that can grow substantially by cross-selling other firm services. Similarly, studies have indicated little to no correlation between Law Review participation (a proxy for academic excellence) and successful rainmaking (a proxy for understanding a client's business). One is not intrinsically a more desirable trait than the other, but at times a firm may place higher value or have a specific need to fill in one area more than the other. Predictive analytics based on factors other than law school and class rank can dramatically improve the probability that a recruit will endure longer than the average. In Bloomberg Law's "Everything You Think You Know About Lawyer Recruiting is Wrong," article co-author Caren Ulrich Stacy declares that "armed with the knowledge of the particular success traits or competencies that exemplify a high performing lawyer, the firm has the ability to employ evidence-based and data-driven tools for lawyer selection."

And the same holds true in a law department. Businesspeople value a counselor who looks to find ways to advance the business and who can quantify degrees of risk, not one whose risk aversion leads to the recurring advice to "make no deals because we can't eliminate all risk." Hiring to criteria other than technical excellence in the company's product specialty may lead to a better business advisor, one who can better instruct outside counsel because they can speak both the language of business and the language of law.

Big Data for Managing a Matter

Many lawyers perusing the above anecdotes will nod their heads, recognizing the inherent logic in employing predictive analytics on the business side of a law practice. But far fewer will acknowledge the ready opportunity to employ such techniques to their own practices. But it's already happening. Venue shopping is merely a tactic employed by litigants to remove a matter to a jurisdiction deemed more friendly to one's side, based on past performance. Jury selection has evolved from art to science, with high stakes cases incorporating psychological profiles and mock juries to identify the optimal approach before even entering the courtroom. The recent increase in legal project management and process improvement tackle these same themes on a more basic level, helping lawyers to understand the repeatability of tasks in even high stakes transactions and litigation. When a client demands a matter budget, essentially what he's asking is for the lawyer to draw on his experience to produce a set of decision trees, informed with probable timelines and costs. Predictability and "lowest cost" are not the same, though many in-house counsel and outside counsel confuse the two. Anyone can lower a rate or demand a lower rate. Only an experienced practitioner can provide informed insights into how a matter may or may not proceed.

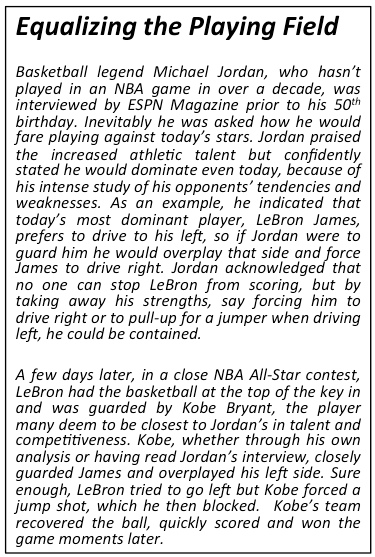

In my recent column in Marketing the Law Firm, an ALM publication, I describe several clever new technology tools in use by law departments and law firms: "New tools are available that collect and synthesize trends across multiple jurisdictions, providing lawyers with insights that may provide an advantage. Case Outcomes, offered by Thomson Reuters, is one such example of big data applied to a legal practice. Says Amy Hrehovcik, New York-based business development manager, 'It’s like breaking down film of an opponent in basketball. If you know your opponent prefers to drive left, you overplay that side and push him right. Lawyers can adjust litigation strategy based on studying the tendencies of opposing counsel and even judges, and offer more informed advice to clients.'" While it takes years to accumulate the sort of jurisdictional knowledge that makes local counsel invaluable in developing trial strategy, new tools are closing the gap.

The Technology Red Herring

It may be helpful to discuss big data from the perspective of those who are often on the front line in these discussions, namely the technologists. Consider a use case: a law firm wants to identify its "ideal" client, and this requires looking across multiple databases such as time & billing, CRM, conflicts, event registration, mailing list, website clients, Chambers and directories submissions, to first capture all of the clients. Then it's necessary to go through a laborious process of matching and de-duplicating this raw client in order to ensure that, for example, "Eastman Kodak" in one system is the same as "Kodak" in another, and to ensure that "FPC Italia" is properly identified as a subsidiary but not Xerox, which is in a related line of business, with plants and offices in close proximity and some movement of executives between the two, but which is a distinctly separate company.

This "data cleansing" takes time and is never really done, because at any time a legal secretary might open up a new matter by entering EK (the suspended NYSE symbol for Eastman Kodak) and introduce yet another variation of the client name. At some point we may want to introduce SIC or NAICS codes to the dataset, add in a more robust corporate tree, combine publicly available data with notes captured from our CRM system, add in a common "key" so future matching processes take less time and then put the resulting data set into a new "data warehouse" where we can run queries against it, though that's a task often restricted to a select few with both access rights and training on database reporting. This is a real challenge for any business, but moreso for law firms which have long eschewed rigorous data management policies in favor of making life easier on partners who want to quickly open up new matters to begin billing. Because of these complexities, many law firm leaders are convinced big data is at heart a technology challenge. They're wrong.

Just Do It

The reality is that while the above technology tasks are often necessary to provide the greatest "big data" payback, there are plenty of techniques and queries that can be run against databases as they exist today, and there are plenty of insights to be drawn from simple manual analysis. The most common objection I hear when proposing predictive analytics projects to law firms or law departments is that they lack resources or tools to do it right. That's not entirely true. While a team of quantitative analysts poring over a robust, structured and fully-indexed data warehouse would be nice, the reality is few businesses have that luxury. And while others hesitate to proceed, those who start with what they have and begin to better inform their business decisions will obtain a competitive edge.

Big data is here. It's entered our lives in the recommendations we see when we shop online, when Facebook or LinkedIn suggests "friends you may know" and when our weekly issue of Sports Illustrated has customized its advertising to appeal to our specific tastes and interests. Law departments are increasingly using big data tactics to identify the "right" fees to pay for different legal matters, and which outside counsel are appropriate for different matters based on non-financial metrics. Legal Process Outsourcing (LPO) companies have deconstructed complex legal tasks into bite-sized and measurable chunks, at once increasing throughput and quality and decreasing costs. And there are numerous law firms beginning to arm themselves with precise data about which clients to keep and which to pursue, which laterals to recruit, which partners to retain based on factors other than origination and what steps are necessary to improve the probability of obtaining a certain legal outcome.

Big data. Those failing to understand it, and those avoiding it, may be making a big mistake.

Note: The mention of a product or service in this article does not constitute an endorsement by the author.

Timothy B. Corcoran delivers keynote presentations and conducts workshops to help lawyers, in-house counsel and legal service providers profit in a time of great change. To inquire about his services, contact him at +1.609.557.7311 or at tim@corcoranconsultinggroup.com.

This represents a

This represents a