Not so fast, in-house counsel, you've also got some work to do!

/Amidst all the virtual ink directed at lawyers for being poor businesspeople, another equally compelling point is too-often missed: clients, particularly in-house counsel, have quite a few shortcomings as well. At the core of my consulting practice is connecting these dots: just as in-house counsel are often unhappy with outside counsel, internal business clients are often unhappy with the in-house counsel. While the struggling economy has given in-house counsel more influence over outside counsel (influence they've always had but haven't exercised), let's not pretend that in-house counsel always know the best way forward. My corporate career had the usual arc when it comes to legal matters. Early on I was exposed to the legal department only via contract or NDA negotiations, or occasionally when some adverse action elsewhere in the business required us to sit through an in-house lawyer's lecture on, say, sexual harassment. As I moved up the ladder, I consulted the legal department on terminations, intellectual property rights, an occasional threat from a disgruntled customer. When I reached the boardroom as a senior executive and eventually as CEO, a role which carried budget responsibility for the legal department and involvement in outside counsel selection, I interacted quite often with the legal department on restructuring, complex joint ventures and acquisitions, major contract renegotiations and other more critical matters.

In my companies, it was typically only after key strategic decisions were made that we brought in the lawyers to help execute the strategy, for the simple reason that we had a lot of in-house lawyers who felt it was their responsibility to thwart our every attempt at business growth. We called them collectively "the Department of No" and we knew which lawyers to avoid and which lawyers to request. Now, I've acknowledged that it was a failing on our part to miss the important role an excellent in-house lawyer can play in the board room. I was lucky enough to have such counselors in my later corporate roles and they were true business people first and lawyers second. To be sure, these lawyers upheld every ethical and professional standard expected of practicing lawyers, but they did so in the context of helping us manage the ongoing risk any business faces, rather than approaching their role as primarily academic or perhaps achieving complete risk avoidance.

In the interests of equal time, here are some suggestions for how in-house lawyers can improve their game and become better partners and trusted advisers to their internal clients. Outside counsel should also take heed, because the more your efforts align with the in-house counsel's goals, the more likely you are to be embraced as a trusted adviser rather than a hired gun.

Understand the business. I've written of my disappointment that some corporate back office functional leaders (ahem, Human Resources) barely understand the business, and this negatively impacts their ability to do their job. Not once, ever, did one of my in-house counsel ask to shadow me or my team for a day to learn our business from the ground up. Several would dial in or sit in on executive leadership meetings, but often their entire contribution in an 8-hour meeting would be to provide a 5-minute update on a pending wrongful termination suit or the status of a bill making its way through Capitol Hill that might pose some challenges. We were lucky enough not to have repeat litigation, but a B-school classmate of mine laments that his company faces the same lawsuit over and over, and it never seems to occur to the lawyers that perhaps there's a systemic issue upstream in the business that could be addressed to prevent future suits. In my consulting practice I advise outside counsel to request a "factory tour," donning a hard hat and walking the floor of a client's business. It's astonishing how often outside counsel return to say that the in-house lawyer who arranged the visit had never taken a tour previously.

Understand the company's risk profile. This is sometimes challenging to explain, but let's start with the caveat that I would never advocate playing fast and loose with laws or regulations that govern a business. But there's a lot about running a business that requires interpretation, and there's a lot about running a business that involves taking risk.  The in-house lawyers need to understand, and be comfortable with, the level of risk a company's executives are willing to take, within certain boundaries. For example, it's not acceptable risk to allow a product out the door that continually fails safety tests, just to get it on shelves in time for holiday shoppers. But it may be okay to enter new markets without a safety net if speed is of the essence. Here's an example: we wanted to launch a new software product in Asia in the '90s, and we had to launch quickly or risk losing first-mover advantage to the competition. We asked the in-house counsel for a down and dirty approach to protecting our IP and launching within 3 months, and what we received -- with the help of some very expensive outside counsel -- was a proposal for 6-month project to protect our IP in every possible jurisdiction and papered in every possible way so as to minimize our risk. Cooler heads prevailed and we settled on protecting our IP in those jurisdictions that had both a means and a will for enforcement (this was Asia in the '90s after all, where piracy was practically government sanctioned!) and the rest, well, we gambled that we could sell enough units to beat the competition before pirates started eating away at our profits. In this case, the in-house counsel and the outside counsel viewed the risk very differently than the businesspeople. We wanted to win in the market; they wanted to protect us at all costs.

The in-house lawyers need to understand, and be comfortable with, the level of risk a company's executives are willing to take, within certain boundaries. For example, it's not acceptable risk to allow a product out the door that continually fails safety tests, just to get it on shelves in time for holiday shoppers. But it may be okay to enter new markets without a safety net if speed is of the essence. Here's an example: we wanted to launch a new software product in Asia in the '90s, and we had to launch quickly or risk losing first-mover advantage to the competition. We asked the in-house counsel for a down and dirty approach to protecting our IP and launching within 3 months, and what we received -- with the help of some very expensive outside counsel -- was a proposal for 6-month project to protect our IP in every possible jurisdiction and papered in every possible way so as to minimize our risk. Cooler heads prevailed and we settled on protecting our IP in those jurisdictions that had both a means and a will for enforcement (this was Asia in the '90s after all, where piracy was practically government sanctioned!) and the rest, well, we gambled that we could sell enough units to beat the competition before pirates started eating away at our profits. In this case, the in-house counsel and the outside counsel viewed the risk very differently than the businesspeople. We wanted to win in the market; they wanted to protect us at all costs.

Allow access to the business people. There are plenty of GCs who do a fine job serving their internal clients' interests and who are, and should be, the primary contact point for outside counsel. But there are others, as the anecdote above illustrates, who have a different mindset than their internal clients. When I work with law firms on legal project management, I stress the importance of knowing the underlying business outcome we're solving for, not just the instant legal issue. Therefore, it's imperative to get to know the businesspeople, not because we want to do an "end run" around the GC, but because for outside counsel to deliver it's critical to know what's at stake and how that perception differs among stakeholders. The GC may not be involved in the "make vs. buy" discussion and so may not know when the cost of acquiring that start-up will be more costly than the company building its own version of the start-up's product. So during due diligence when we find IP infringement, or environmental contamination at the target company headquarters, either of which requires costly remediation, the GC and outside counsel might start to remediate rather than adjust the scope and budget for the businesspeople, who might decide to walk away instead. Outside counsel who use these relationships to try to avoid the GC deserve to have their hands slapped. But GCs who inappropriately limit contact with businesspeople out of a misguided "gatekeeper" mentality or, worse, for their personal job security, should be slapped too.

Embrace continuous improvement. I can't tell you how many weeks of my life (and how many sales!) have been lost waiting for the in-house lawyer to approve a non-disclosure agreement hung up on some unimportant point that we had conceded countless times previously, or how many negotiations went south because our in-house counsel was too jammed up to work quickly so the faster, nimbler competitor won the order. We all understand time constraints caused by volume. But businesspeople also recognize that activities occurring in high volume are ideal candidates for process improvement. Mark Chandler has automated numerous functions in Cisco's law department using process mapping and technology solutions to eliminate unnecessary steps, speed cycle time and bring the legal function closer to the business objectives. I've heard hundreds of similar anecdotes from less visible GCs during the many in-house counsel workshops my team produced. The key difference is to treat the law department as a business function subject to the same business process improvement mindset found everywhere else in the business, and not treat it as "law firm lite," a not-uncommon default approach for lawyers trained as partners in big law firms.

Make decisions based on data. Most law departments employ some electronic billing. (If not, turn from your screen right now and pick up the phone and begin the process of implementing e-billing!) Whether the in-house team relies on years of its own billing data, harvested from multiple firms across multiple matters, or whether it augments the analysis with data culled from an aggregated and anonymized data warehouse offered by the e-billing provider (here or here), the key takeaway is that there is sufficient information available to drive better decisions - from legal budgets, to risk exposure, from expected fallout during a restructuring to expected gains from a convergence effort, and so on. Most businesses have analysts in the finance or strategy or marketing departments offering feedback and recommendations to the executives. No law department should be without analysis, if not its own analyst. (I am moderating an upcoming panel on this topic here).

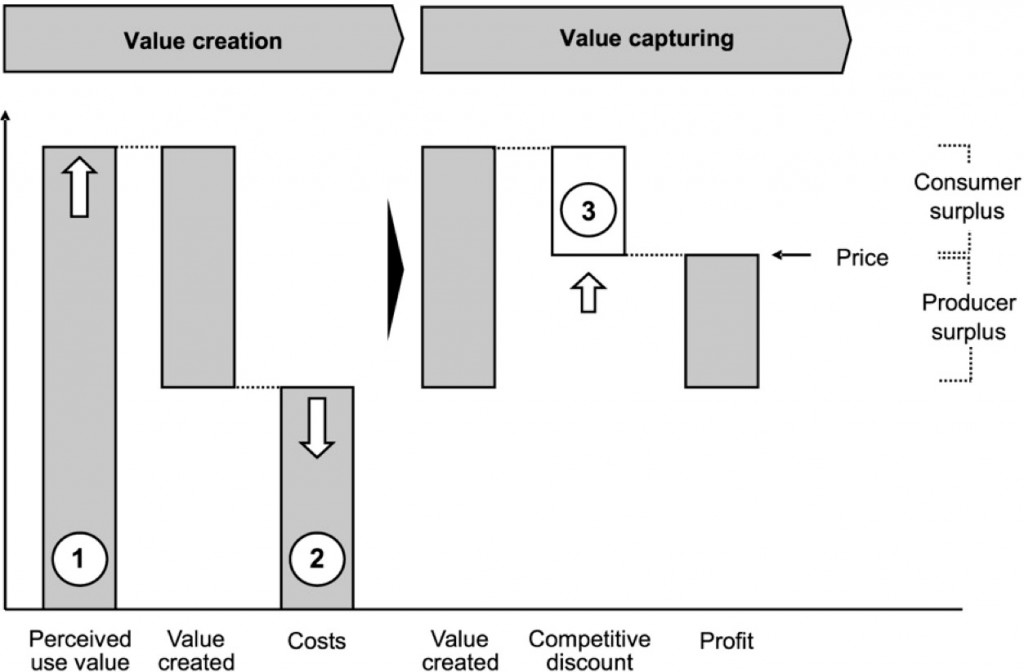

Hire outside counsel based on expertise and value. In 2009 when the CFO cut the law department budget by 30% and demanded the GC "do more with less" without incurring additional risk or delaying throughput and, by the way, added a clause to the GC's compensation scheme that tied his or her annual bonus to staying within the thinner budget, issues pertaining to legal spending became very personal very quickly. Loyalty went out the door along with many firms whose relationship partners believed their client relationship was sacrosanct... and whose billing rates were therefore set accordingly. As we've seen, law departments have aggressively taken the reigns of late. But many GCs, rather than rely on data to inform their outside counsel decisions, take a shortcut and substitute discounts for analysis. Wielding a large club and demanding discounts from favored suppliers is, sadly, a tactic that many businesses employ -- including law firms who have employed their own procurement function as their own fortunes have suffered. But just as procurement isn't focused solely on low cost, GCs shouldn't mistake discounts for increased value. Just as we advise outside counsel to partner with clients, the clients have to partner with outside counsel. You can't ask for a legal budget if you won't share voluminous information about the matter, or set of matters, you need addressed. You can't refuse payment for scope creep if you won't help define the scope up front. It's a lot easier to conduct the analysis described above when there's full disclosure from both law firm and law department, and from this you will distinguish the capable firms from the wanna-bes, the firms whose subject matter expertise informs their pricing decisions from the predatory pricers, the firms measuring the relationship over the long haul from those looking to generate profit one matter at a time, and so on.

The key takeaway is that we're all in this together. Listening to in-house counsel endlessly bash outside counsel is not productive if the in-house counsel aren't helping to craft solutions. And while we businesspeople don't typically hold panel discussions at conferences where we bash the in-house law department, we're often just as unhappy with our lawyers, and we're just as obligated to step in to improve things. Connecting the dots between the three parties isn't easy, especially with compensation plans and long history which seem to create zero-sum games -- when one party "wins" another has to "lose" -- but these are solvable problems. I, for one, am eager to get started. Who's with me?

Timothy B. Corcoran delivers keynote presentations and conducts workshops to help lawyers, in-house counsel and legal service providers profit in a time of great change. To inquire about his services, click here or contact him at +1.609.557.7311 or at tim@corcoranconsultinggroup.com. – See more at: http://www.corcoranlawbizblog.com