Demystifying Outsourcing for Corporate Counsel

/I was recently asked to contribute an article on the topic of outsourcing to the corporate counsel section of the Philadelphia Legal Intelligencer, the oldest law journal in the United States. Below is the published article copy, followed by additional commentary developed while conducting background research for the article.

The Legal IntelligencerBy Timothy B. Corcoran

September 23, 2009

Corporate law departments face an unprecedented level of pressure to reduce costs, to do more with less and to deliver a quality legal product to internal corporate clients. In days past, as the saying goes, the chief legal officer would offer executive management a choice: “We can do the work well, we can do it quickly or we can do it cheaply. Pick two.”

Today’s CEOs want it all, and who can blame them? Every business function faces a relentless drive to eliminate defects, improve production capacity and accelerate time to market. Law departments have been somewhat sheltered from these pressures, in part because of the unpredictable nature of legal issues, much to the chagrin of executive management. Adding to the tension is the trickle-down effect of an unprecedented growth rate in law firm revenues over the past 10 years, which, according to a recent study by the Corporate Executive Board, increased 75 percent while other supplier costs increased by an average of 25 percent.

But is it only about cost? Will executive management be satisfied if the CLO extracts substantial discounts from its primary law firm suppliers or migrates some work to lower-cost regional law firms? According to some business leaders, this will simply no longer suffice.

Imagine the boardroom presentation by the chief marketing officer in which he or she provides a two-year revenue outlook for multiple global product lines, reflecting varying levels of demand and market share. This is followed by the head of manufacturing, whose production forecast incorporates the probability of interruptions in raw material supplies, ranging from droughts in South America to pirates off the coast of Africa to labor unrest in Asia. The treasurer, in turn, presents a plan designed to hedge against the risk of currency fluctuations.

Then the chief financial officer presents an eight- to 10-year cash flow projection for a pending acquisition. Raise your hand if you would like to be the general counsel in this setting who admits that since few variables managed by the legal function can be predicted with any certainty, and because of increasing supplier costs, the legal department will be submitting a 20 percent budget increase over last year.

Small wonder, then, that the drive for improved metrics and efficiency has arrived in the law department with some fanfare, and not a moment too soon. One recent innovation available to the chief legal officer is outsourcing, or assigning work to specialist providers in the United States and abroad that offer non-traditional legal services.

But is this really so new? Hasn’t it been the case all along that the company, which manufacturers widgets or develops software or provides business services, has outsourced its legal needs to specialist providers, first within the legal department and then to outside law firms? The corporate legal function serves both an operational and strategic role, but there are few business owners who dream of a sizable and well-run legal department as a strategic asset in the same way that they dream of, say, a world-class sales force. So let’s acknowledge that we’ve already been engaged in outsourcing, and then let’s take a harder look at what new options are available.

First, it’s helpful to define terms. Outsourcing refers merely to the delegation of work to another organization, where it can presumably be carried out more efficiently. Offshoring typically takes place when the other organization is in another country. Insourcing involves delegating work to another specialized group within the same organization. The delegation of work to outside counsel is an example of outsourcing, as is the use of contract lawyers to handle overflow volume in document review. Hiring legal research experts in India is an example of offshoring, as is moving a customer service call center to Ireland or a graphics design team to the Philippines. And insourcing, of course, is exactly how most companies perceive the legal department — an internal organization with specialized skills.

Most companies, and indeed most law firms, have engaged in business process outsourcing, or BPO, for some time. Whether it’s operating the corporate cafeteria or the mailroom or hiring a third party to ship goods, organizations have learned that subject matter experts can generally take over these tasks with minimal fuss and at a lower cost.

Many law departments have found that hiring contract attorneys provides an excellent opportunity to test their appetites for outsourcing, before establishing any offshore relationships. Market research firm Gartner estimated the 2007 BPO market to be $173 billion. The potential for cost savings in the legal function is also enormous, in relative terms. In a recent move that raised eyebrows in the global legal market, Australian-English mining conglomerate Rio Tinto announced that it expects to save $25 million annually, or 20 percent of its legal budget, after hiring a legal process outsourcing, or LPO, firm to perform routine legal tasks.

Critics declare that legal matters are much more strategic in nature than administrative functions and can’t be easily delegated. After all, do you really want the company to rely on the lowest-cost provider when it comes to a “bet the company” transaction or litigation? But therein lies the issue at the heart of the matter. Chief legal officers have long known that even the most important legal issue facing the company is composed of multiple smaller components, many of which involve routine, commoditized tasks. Law firms are expensive suppliers in part because they tend to treat all aspects of an important transaction as high value and high cost. With some exceptions, most lawyers believe their particular area of expertise is a premium offering housed within a firm that provides other premium services. It’s other lawyers in other firms who provide commodity services.

The truth, as usual, lies somewhere in the middle. The legal profession is not typically viewed as progressive in its business practices. However, the overwhelming growth of LPO has raised a number of questions about the practicality and ethics of relying on outsiders to provide legal services. Isn’t it a disservice to the client, possibly even unethical, to rely on low-cost providers for important legal matters? Not so fast, according to the American Bar Association. In Formal Ethics Opinion 08-451, the ABA declared: “There is nothing unethical about a lawyer outsourcing legal and non-legal services, provided the outsourcing lawyer renders legal services to the client with the ‘legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.’”

So how does a chief legal officer ensure a quality work product from an outside provider? The following are a few suggestions:

• Test-drive the work product of an LPO provider on a single project before engaging them for the long term. Quality providers will invest in significant ongoing training for their workforce and should welcome the opportunity to demonstrate their quality.

• Develop objective measures of quality. This can be achieved by working with the LPO to develop a detailed model of operating procedures for the required work. Once these procedures are in place, it’s easy to establish a quality template that tracks deviations from the desired outcome.

• Institute standard project management techniques like those used every day in most organizations to manage technology initiatives and manufacturing operations.

• Manage LPO relationships with diligence. Don’t lose focus after the initial engagement discussions. Be aware that your LPO staffing team may change over time and insist on the same level of training for team members rotated in later to maintain consistent quality.

• Consider cultural implications. If you offshore, it’s important that your LPO liaison have solid English speaking skills as well as an understanding of the local culture. And conversely, you must communicate your own company’s culture and objectives.

In the end, outsourcing can generate far more than labor arbitrage. Ray Bayley, co-founder of Chicago-based NovusLaw, in an interview on the “Adam Smith, Esq.” blog, discarded that as the primary objective of LPO: “We’re not in the business of ‘lifting & shifting:’ Taking what’s done here and moving it to a cheaper jurisdiction in order to do it the same way. That’s a brute force approach that adds nothing to the quality, reliability, and repeatability of the work.” Instead, for example, a routine service like document review can be studied and modeled and the multiple variables influencing the cost can be identified and quantified, thus reducing the cost and adding efficiency and value.

What’s to prevent a legal department from embracing this sort of “Lean Six Sigma” approach to analyzing and improving its own legal services? Nothing at all. In fact, legal departments that adopt these techniques will be better positioned to identify, evaluate and select appropriate outsourcing providers. Among the hidden benefits to outsourcing is the familiarity the client generally gains regarding business process improvement techniques. Once ingrained into an organization’s operational mindset, it’s difficult to revert to a blissfully unaware state where efficiency and quality are abstract concepts.

It would be remiss to conclude without addressing the emotional response outsourcing and offshoring can sometimes generate. Whether from organized labor or politicians or trade groups, it’s not uncommon to hear opposition to outsourcing, particularly when it’s perceived as sending jobs overseas. The Economist recently declared offshoring to be a win-win phenomenon, at least on a macroeconomic scale. But the backlash has led to a reversal in some industries, such as the return of technology call centers that lowered costs but also lowered customer satisfaction rates. Many LPO providers offer services across the United States and in English-speaking countries to help mitigate these very concerns.

Human nature tends to question that with which we are unfamiliar. And to many, it’s an uncomfortable realization that some sophisticated legal processes can be analyzed, broken down into constituent parts, delegated to disparate providers and returned with higher quality, lower costs and greater predictability than we’ve been accustomed to. But with change comes opportunity. Imagine tomorrow’s boardroom presentation by the chief legal officer, who can now submit, with some certainty, the costs and implications of ongoing legal matters. Even better, imagine having the capacity to focus on matters of more critical long-range interest to the company, demonstrating that a well-run legal department is a significant strategic advantage. •

Copyright 2009. Incisive Media US Properties, LLC. All rights reserved. The Legal Intelligencer

Click here to see the article on the Legal Intelligencer site. (Subscription may be required.)

There are numerous sources to help understand the changing legal landscape, with more arriving each day. I found a white paper “Future Law Office” distributed by Robert Half Legal, the legal professional placement division of Robert Half International, to be very informative. While its position may be considered somewhat self-serving, the white paper describes the very real use of contract lawyers by in-house legal departments as a means of testing whether they can obtain quality legal work product through non-traditional means. In fact, this has the same effect as the approach taken by many corporations who “test” potential new hires by first hiring them as a temporary employees. And why not test the goods before purchase? Rocky Dhir, President of Chicago-based Atlas Legal Research, invests a significant portion of his resources in training, so he encourages potential clients to take a test drive. “Actually test the work product of any LPO provider before engaging them long-term.” Selecting wisely is critical, because “picking the wrong firm can end up being more expensive.”

Suhasini Sakhare of Zeta Intelex recognizes the challenge in demonstrating quality in a profession that tends to not have objective measures of quality. Her organization follows a rigorous process to ensure the highest-quality output, using as a foundation very detailed operating procedures based on the client’s needs. These are often developed through repeated observation, as “most clients who should be intimately familiar with their own legal processes actually aren’t.” Once these procedures are in place, it’s easy and intuitive to establish a quality template that tracks all deviations from the desired outcome. It may come as a surprise to Biglaw partners, but not to many clients: the quality of the legal work can actually be improved by outsourcing due to the intense focus and quality controls in place. Of course Biglaw legal work product is routinely high quality, but absent objective measures of quality clients are no longer willing to pay high rates on reputation alone.

It’s not as challenging as one might think to implement quality control processes within a law firm. This is project management 101, after all, and the techniques aren’t limited to managing technology initiatives and manufacturing operations. Ron Friedmann, senior vice president of marketing for Integreon, ran practice support for a large law firm and was CIO of another. In his view, “There are many parallels between managing projects and managing a company’s legal strategy.” He elaborates, “Law departments can reduce costs by explicitly acting as general contractors to solve company legal problems. Like any GC (general contractor that is, not general counsel), a law department should consider what resources it employs full time and what it sub-contracts.” I’d go even further and say that outside counsel can also act as project managers and even general contractors. Why couldn’t a Biglaw relationship partner serve his clients needs by coordinating internal services with outsourced services on behalf of the client? We do it already, quite regularly… local counsel, anyone?

Like any relationship, the connection between an outsource provider and an in-house legal department takes time and effort to maintain, even with good metrics and processes in place. Stephen Seckler, a lawyer and consultant, advises IPEngine, an IP outsourcing firm with operations in India. “It’s important that your liaison have solid English-speaking skills as well as an understanding of the local culture.” John Roney, President of Applied Dynamic Solutions of New Jersey, has long experience with managing outsourced IT projects, and suggests the lessons are universal. “Many projects get off to great starts but when the spotlight is off, there is often a break in the continuity of the team, and sometimes new team members don’t receive the same rigorous training.” He also urges companies to treat the outsource vendor as a part of the team. “This means attending staff meetings to understand the company’s culture and grasp the company’s objectives.”

We’ve focused primarily on the challenges facing corporate legal departments and Biglaw. “Much of the LPO industry is geared to serve the needs of large corporate legal departments and large law firms, but there’s a lot more to it,” declares Ed Scanlon, president of Total Attorneys, which provides contract lawyers and paraprofessionals to handle general legal work overflow and specialized services, such as bankruptcy case management, to small law firms.

The results so far suggest that non-traditional means of delivering legal services, via contract lawyers or outsourcing or offshoring, should be an essential aspect of a law department’s tool kit in the future.

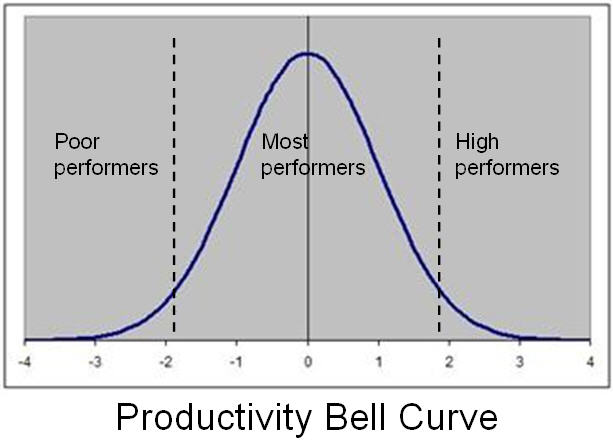

in one area while known incompetents in another area are unaffected. Break through the artificial barriers we erect with org charts and identify the poor performers across the board, and let them go first. This requires a certain business-first attitude that is sadly lacking in many managers, but in the long-run it's better for the business when every layoff shifts the productivity bell curve to the right rather than eliminate high performers due to some misguided sense of fairness. (The concept of fairness is often

in one area while known incompetents in another area are unaffected. Break through the artificial barriers we erect with org charts and identify the poor performers across the board, and let them go first. This requires a certain business-first attitude that is sadly lacking in many managers, but in the long-run it's better for the business when every layoff shifts the productivity bell curve to the right rather than eliminate high performers due to some misguided sense of fairness. (The concept of fairness is often