Legal Budgets and Corporate Budgets - Why Predictability Matters

/I recently met with a group of law partners to discuss the feasibility of increasing the firm’s billing rates for the coming year. Normally this doesn’t require a discussion; the firm traditionally raises its rates 5-6% every year. And normally this takes place in January once the prior year's books are settled. This year, however, and to the partners’ credit, they questioned the optics of raising rates at a time when most of their clients are still suffering from the impact of the global economic meltdown, or the Great Reset, as Bruce MacEwen calls it. As we debated the pros and cons, it was apparent that the partners had very little understanding of the impact an increase to their billing rates might have on a client. In fact, none of the partners had worked in a corporate setting previously so they had no real insights into the typical corporate budgeting process. Perhaps a peek behind the curtain may help inform this discussion, as it’s a process full of surprises to law firms that often have rudimentary budgeting processes in place, if at all.

The first surprise is when budget discussions commence. Assuming the fiscal year corresponds with the calendar year, most businesses start preparing budgets in August. Yes, in August prior to the budget year. It takes time to develop a budget from the ground up. In days past budgeting may have been approached as an exercise in what’s different or, in other words, starting with last year’s budget and merely adding new items and deleting old items. No more. Now there’s an expectation that every budget must start at zero, and from this starting point we add in each and every cost until we identify the total budget needed. And then we start paring it back.

Many lawyers operate under the delusion that the practice of law is inherently and infinitely variable, meaning that unlike other business functions one cannot predict legal costs with any certainty. This opinion is often held by outside counsel and in-house counsel alike. Imagine the plight of the General Counsel: she doesn’t know how many deals the business executives may initiate in advance when even they don’t know. She has no insight into what product liability suits the company may face, or what type of employment actions will be raised. For litigation already underway, she can’t possibly predict the next move the adversary may make, so by definition she can’t budget for how she’ll react. And even acquisition due diligence may reveal complications that are impossible to predict. These are reasonable concerns, but they fly in the face of the number one rule in business: no surprises.

One can make mistakes when climbing the corporate ladder. One can make some mistakes again and again. One can even make colossal mistakes that cost the business money. But the one mistake anyone aspiring to reach the board room can’t make again and again is surprise. Corporations, both public and private, thrive on certainty. Forward-looking statements to shareholders and analysts must be based on a reasonable estimate of future performance, or else the stock price will suffer in the market. Even private companies that don’t publish earnings must have predictability to properly allocate capital. For business leaders to establish priorities they must have the facts, and the worst crime is to provide inaccurate information because this leads to making poor business decisions.

Another surprise may be that erring on the side of caution can be as egregious a mistake as overestimating performance. Imagine the Senior Vice President of Marketing who submits a revenue forecast estimating $275 million in sales, knowing full well that the business is on track to deliver $280 million in sales. On paper this looks clever, because bonuses increase with overachievement, and everyone looks good when we beat the targets, right? However, it’s not uncommon for the CEO and CFO to punish the business leader who builds in too much revenue cushion, because we might have made different decisions about our allocation of capital if we knew that we had more to work with. A critical project with great long-term potential may have been delayed or tabled because we didn’t have sufficient investment available. (The worst offenders allocate a reserve that benefits only themselves.) Obviously there’s also punishment for missing the targets, particularly when it results from poor planning rather than external market events.

But how do they do it? How do corporate executives weigh numerous variables to establish an accurate forecast? After all, don’t most business functions carry some level of uncertainty? Think of the head of manufacturing who must predict costs despite the possibility of critical supplies being hijacked by Somalian pirates, or labor unrest in the fields of South America, or political unrest in the Middle East impacting oil prices which in turn have a material impact on the costs of transportation in our supply chain. And what about the corporate treasurer who has to predict the impact of currency fluctuations or interest rates on the company’s cash flows, in order to hedge against this. Our head of Marketing has to examine multiple products across the spectrum of the business cycle, use a little game theory to predict what the competition might do in response to our new product launches, potentially even identify which customers are at risk before the customer even begins to explore substitutes, and build a revenue forecast amidst ever-changing market demand.

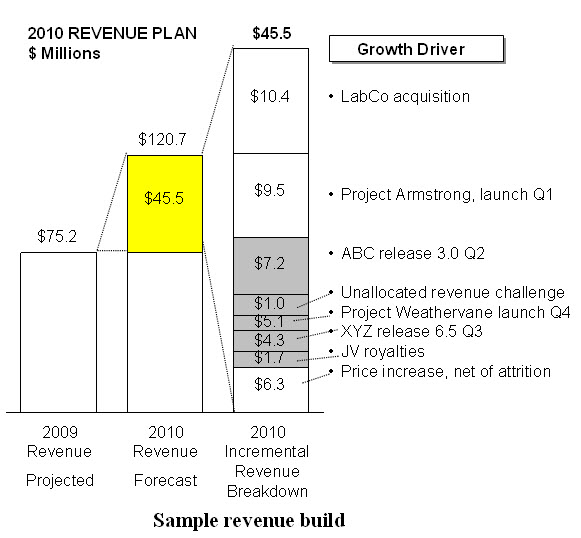

There’s no magic formula. These business leaders build their forecasts block by block, inch by inch, starting first with the known – in the case of sales, perhaps we first identify guaranteed revenue from committed customer contracts, or in the case of manufacturing maybe we look at commodity materials where we have multiple suppliers to ensure sufficient flow and predictable prices.  We then move on to the harder calculations, one by one looking at product revenue in each jurisdiction, perhaps customer by customer; or examining links in our supply chain where we have limited redundancy and therefore greater risk. Piece by piece we establish a forecast that builds from certain to less certain, but even with the less certain we identify the likely ranges and provide confidence levels based on identified risks.

We then move on to the harder calculations, one by one looking at product revenue in each jurisdiction, perhaps customer by customer; or examining links in our supply chain where we have limited redundancy and therefore greater risk. Piece by piece we establish a forecast that builds from certain to less certain, but even with the less certain we identify the likely ranges and provide confidence levels based on identified risks.

So you can imagine the amused chuckles in the board room when the Chief Legal Officer throws up his hands and tells his colleagues that the legal function contains too many variables to possibly establish a budget, so instead he’ll take last year’s budget and add 20% -- to accommodate law firm rate increases and other variables – and he’ll only come back and ask for more if something changes. Gone are the days when this was amusing. Now a General Counsel may be shown the door if he can’t apply some rigor to the legal budgeting process. This also explains the increased involvement of procurement officers in the selection, and management, of outside counsel. This is a clear sign that CEOs and CFOs don’t fully trust their lawyers to extract more value at a lower cost from the in-house legal staff and suppliers, so they’re putting someone at the table whose sole objective is to reduce costs. Or they wish to, as the saying goes, trust but verify.

These budget calculations and conversations start in August, are debated endlessly through September, and begin moving up the approval chain in October. There are numerous revisions, typically, as you might expect, requiring all cost estimates to go lower and all revenue estimates to go higher. But there’s a balance to be achieved between optimism and realism. Newly anointed business leaders tend to believe that they can extract unnecessary costs that their predecessors overlooked, or that they can rally the troops to commit to higher revenue performance. Entrenched civil servants throughout the corporation strenuously object to these stretch goals, and work diligently to maintain the status quo, with sufficient safety valves in place for when something goes wrong. This can be invigorating, and it can be confounding, but in the end the corporation signs off on its revenue and expense budget for the coming year, typically by early November.

As my group of law firm partners discussed corporate budgeting, a few light bulbs appeared above their heads. One corporate partner recalled receiving a letter in late October from a key pharmaceutical client indicating that they would not accept fee increases from any outside counsel in the coming year. She recalls wondering why the letter was sent in October, months before most law firms issue rate increases, but it now occurred to her that the corporation’s budgets must have been locked by then. Another partner realized that even when the economy is humming along nicely and law firms have the latitude to increase rates, the fee increase letters are potentially six months out of sync with the client’s budgeting process! “No wonder clients claim we don’t understand their business,” he observed. One of the partners added some levity by suggesting that the annual fee increase letters should go out earlier, say in July. Another had us rolling in the aisles when she suggested that since law firms always raise rates, and clients know this, perhaps it’s the client’s obligation to build in these expected increases in their August and September forecasts. When we realized she was serious, we ended up rolling our eyes. In some segments in some industries, the suppliers can set the price and require the buyer to meet the price, or else not get the product. (Have you ever tried to haggle significant savings on a Mercedes?) There are a few law firms with such pricing power. Let’s be clear: despite your desire to occup this space, the odds are your firm is not one of these.

But does this budget process really result in certainty? After all, we’ve all seen – or we’ve owned stock in – companies that miss earnings forecasts. In reality, one never eliminates surprise. But we can get a lot closer by minimizing it. There’s a formal process to deal with the inevitable changes that occur in most corporations. It’s called a reforecast. It may come as a surprise that most companies begin revisiting their revenue and expense budget numbers in early January. After all, what can go wrong in the first few weeks of the year? However, think back to when we began compiling our forecasts. We weren’t even done with Q3, let alone Q4, so many of our assumptions for the coming year relied on assumptions for how we’d conclude the current year. And guess what, things have changed since we incorporated those assumptions.

A reforecast is a formal process to revisit our assumptions, to look at costs that exceed expectations and revenues that fail to meet expectations. And vice versa. In many corporations this process repeats itself several times a year, often corresponding with the quarterly earnings report in public companies, and in recent years this process might happen 6 or 7 or even 12 times a year. And it’s not simply indicating that revenues are falling short or that expenses are trending high and then receiving forgiveness on the goals. That would be cool. No, instead every functional leader has certain levers to pull to meet the agreed-upon expectations even when there are material changes in costs or revenues. On the revenue side, perhaps we launch a sales contest, or lower prices to increase penetration. On the cost side, perhaps we seek alternative suppliers, squeeze the suppliers we have, or reduce costs elsewhere by reducing staff. Often the reforecast process surfaces significant trouble in one division that will be impossible to make up, so other divisions receive an involuntary revenue or cost surcharge to make up the difference. This can be painful. No business leader in the midst of stellar performance, overachieving on every goal, or even those barely meeting expectations, likes to terminate valued employees or table a valuable project because some other division failed to meet expectations. But it happens.

To add more enjoyment to the budgeting process, most corporate executives have a portion of their annual compensation based on their ability to manage to their budget. For example, the company may exceed its revenue and profit targets, the share price may exceed analyst expectations, the division may have enrolled a record number of new customers, but the divisional leader will lose 30% of his bonus because costs were over budget. Those running the legal function are late arrivals to this party, but it’s becoming a material factor in their compensation now.

Recently I observed a panel of General Counsel discuss their likes and dislikes with outside counsel. One GC remarked, much to the amusement of the roomful of outside counsel: “If my legal budget goes over plan, at least we’ll save money on my bonus.” The GC didn’t laugh. He was deadly serious. The message he was trying to convey is that the late invoice, the one you generate only at the end of the billing period, the one that reflects billings 40% over the original estimate, the one that you’ll accompany with a brilliant, well-crafted memo explaining the 58 reasons why costs exceeded your original estimate, may literally cost him his family’s summer vacation rental, or a semester of his daughter’s college tuition, or the swimming pool he planned to install in the Spring. Just as with the General Counsel who remarked, “If I don’t find a way to manage the legal function with a lower budget and without compromising quality and throughput, they’ll find someone who can,” your client needs you to be part of the team.

Perhaps these insights into the corporate budgeting process will shed some light on why your clients are so darned insistent on predicting legal costs. In many cases, predictability trumps total spending, or, in other words, you can charge premium rates as long as you ensure that the fees are not surprises. You may also question whether a fee increase is necessary this year, particularly since your client has fewer levers available to adjust for your increased cost. Perhaps you can do a better job of estimating legal costs for your next project. The project management techniques used in other business functions apply to predicting and managing legal costs, but that’s a topic for another day.

As another General Counsel said to me recently, “I know a lot of firms that are capable of handing my legal work. I’m sure there are many more that I don’t yet know. What wins me over isn’t always low rates or discounts, it’s finding a firm that really understands that challenges I face in my business – and this includes not just the legal issues I face in my marketplace, but how I have to manage my legal department as a business. If I can find a firm that understands what life is like in my shoes, that firm will win my loyalty.”

What do you say, are you up for it?

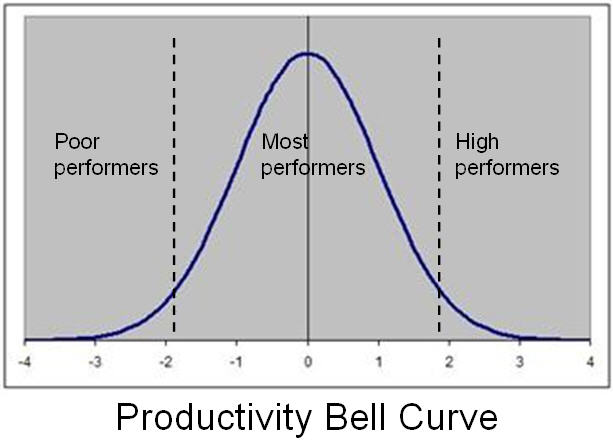

in one area while known incompetents in another area are unaffected. Break through the artificial barriers we erect with org charts and identify the poor performers across the board, and let them go first. This requires a certain business-first attitude that is sadly lacking in many managers, but in the long-run it's better for the business when every layoff shifts the productivity bell curve to the right rather than eliminate high performers due to some misguided sense of fairness. (The concept of fairness is often

in one area while known incompetents in another area are unaffected. Break through the artificial barriers we erect with org charts and identify the poor performers across the board, and let them go first. This requires a certain business-first attitude that is sadly lacking in many managers, but in the long-run it's better for the business when every layoff shifts the productivity bell curve to the right rather than eliminate high performers due to some misguided sense of fairness. (The concept of fairness is often